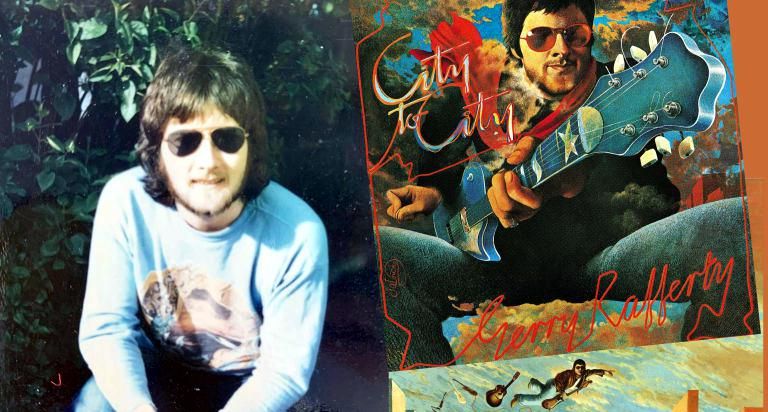

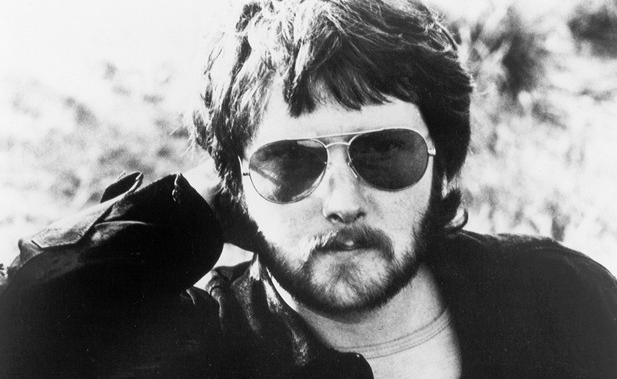

BLOG | GERRY RAFFERTY ‘City To City’ album & ‘Baker Street’

By Phil Harding | Editor John Paul Palmer | 05 October 2021

Phil Harding revisits unreleased mastertapes of some

of his earliest work as a young engineer at The Marquee Studios – mixes he

created of Gerry Rafferty’s highly-acclaimed ‘City To City’ album (released in 1978),

which includes the iconic international hit ‘Baker Street’. The album sold in the millions around the world and reached No. 1 in America. Phil looks

back at his work on the project during 1977…

This

first one has been influenced by the fact that it was mentioned in the recent podcast that I recorded with producer

Steve Anderson. I’ve done many interviews over the years and quite a few

podcasts in recent times, but no one has ever asked me about my work on the

Gerry Rafferty album ‘City To City’ until Steve did (although that bit was

actually edited out of the final podcast!). This coincides with the journey that

I’ve been on since 2019, digitally archiving my reel-to-reel analogue tape

collection. Having completed the transfers of many 4-tracks of my own demos and

24Club band recordings, I’ve since moved on to my stereo tape collection of

various 70s and early 80s projects that I engineered. Steve began the question

with crediting me for mixing the ‘City To City’ album. (Hear the full album here). I immediately had to correct him by stating that the final album does not

contain the mixes that I did at The Marquee, and that my contribution was

slimmed down to some minor overdubs that we recorded whilst going through what

turned out to be the first set of mixes (which were not finally used). Looking

back at these sessions after all this time, I think it’s good to call them

‘work in progress’, although at the time, it seemed like ‘failure’ to me.

I

probably had little or no idea who Gerry Rafferty was back then, but I’m sure I

would have been familiar with his 1972 UK/US top 10 hit as part of the band

Stealers Wheel, ‘Stuck In The Middle With You’ (Wikipedia entry). In

1977, I was only 20 years old and still very much a junior engineer. Looking

back at this now, it was surprising that I was chosen by the studio for the

sessions. I had been training for four years by that time, under the wing of

some of the tremendous engineers at The Marquee Studios – Phil Dunne, Geoff Claver,

John Eden and my fellow junior engineer, Steve Holroyd. I can only assume that they

were all busy on other projects down in Studio 1.

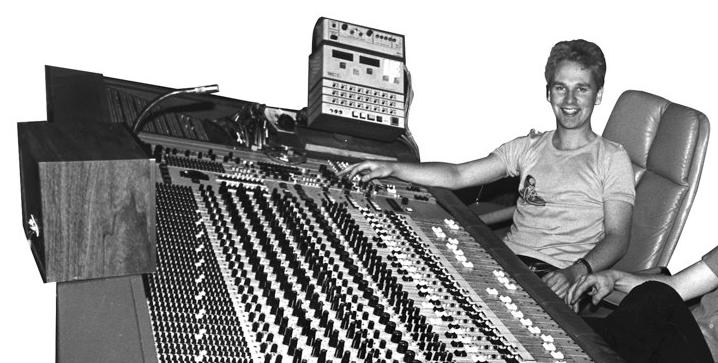

These

Gerry Rafferty sessions took place in Studio 2, which was a small and intimate

mix room designed by Eastlake Audio. Luckily, it had a small ‘overdub booth’

to the side. After an aborted first attempt by The Marquee to build a second

studio on the first floor, the re-design of the Marquee Studio 2 mix room was

completed by Eastlake Audio in around early 1977. I had engineered a few

sessions in there, some experimental, as well as the Berni Flint sessions that

led to his hit single ‘I Don’t Want To Put A Hold On You’ that same year.

The

studio control room was very small, with barely enough room for three people

behind the MCI JH-500 mixing console. For the Gerry Rafferty sessions, I was on

the right-hand side, controlling the tape machine remote control and the ‘master

fader’ and ‘group fader’ section of the console. Co-producer Hugh Murphy was

seated in the middle, and Gerry (also co-producer) was happy to be at the end,

on the left-hand side. My memories of the sessions are pretty vague, but it

seemed that Hugh was in charge of these mixing sessions. He was happy and

confident controlling the fader balances, but would leave most of the EQ

processing on the board and the external processing hardware, such as

compressors and so on, to me. We had two reverb plates available to us, but

very little else. Hugh had the vision of what was needed for the mixes, and was

continually checking with Gerry, who was very relaxed and clearly trusted Hugh.

I got the impression that Gerry’s co-production role had been completed

throughout the recording process and he was happy to take a back seat

throughout this initial mixing stage.

Some

overdubs were added during these sessions in the small-but-quite-comfortable overdub

booth, to the right of the control room. Percussion overdubs were added to

tracks like ‘City To City’, and some backing vocals were also added to a couple

of songs. It seemed as though these were last minute additions that had maybe been

missed at the main recording sessions at Chipping Norton Studios (in

Oxfordshire), where the bulk of the album had been recorded. No extra vocals

were added by Gerry and he seemed very happy with what had already been

recorded.

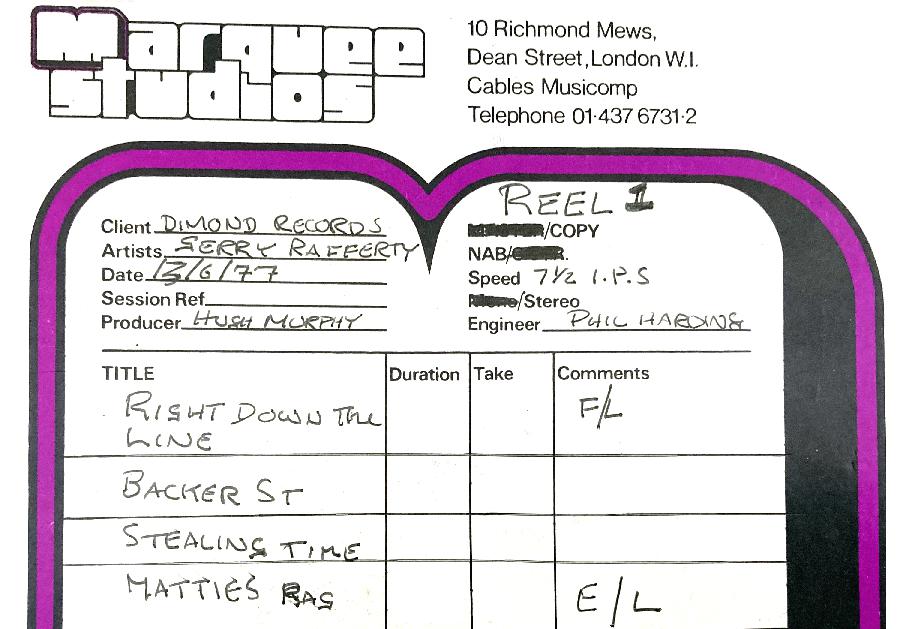

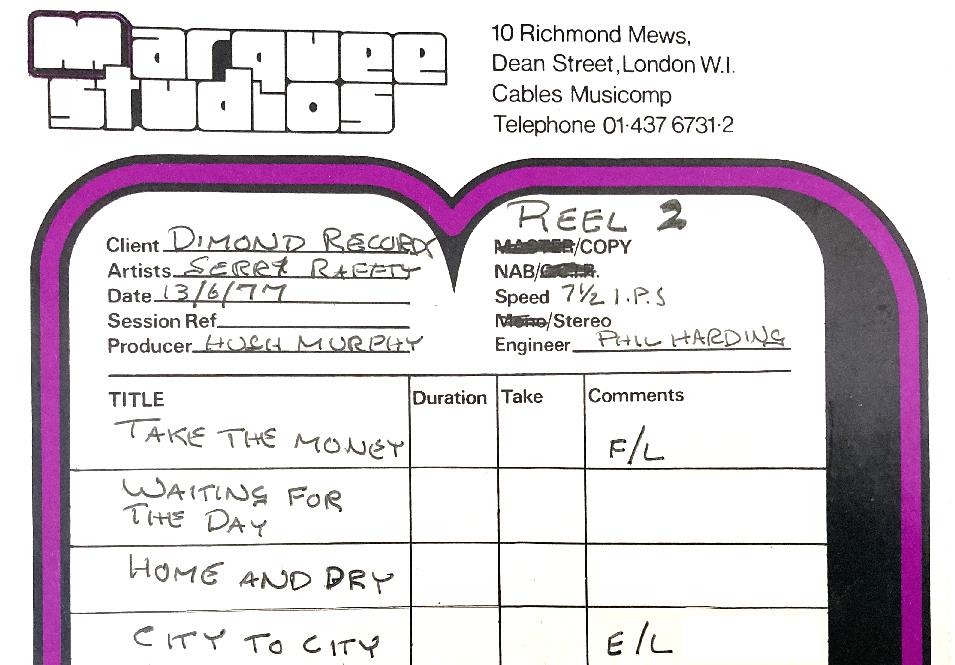

The

date shown on the two Marquee tape boxes from my analogue collection is ‘13th

June 1977’. This would have been the ‘copy’ date of these mixes, and I imagine

we would have been working on these eight tracks from late May 1977. It’s

interesting to note from my copy tapes that there are only eight songs, and that

‘Take The Money And Run’ was not used on the ‘City To City’ album, but appeared

on the ‘Night Owl’ album released in 1979. Other tracks, such as ‘The Ark’,

that were on the final ‘City To City’ album are missing from these sessions,

and I don’t recognise the song when listening to the final album. Either we

didn’t get on to mixing that in these ‘work in progress’ sessions, or it was

recorded after the Marquee sessions.

My

memory of the final session was a typical ‘album playback’ set-up for the

manager, label and musicians that could make it in. As I’ve said, space was

tight, so this was an uncomfortable event, where only a couple of people could

sit in the ideal central listening position. My lasting memory of this session,

where all eight tracks were played, was that the bass player made a very

damaging remark at the end, saying something like ‘I’ve heard this room can’t

be trusted’. That created an edgy atmosphere for the people present, and I did

my best to defend the quality of the room acoustics and their reliability, but

once someone says something like that, it is very difficult to recover from it.

I think that planted negative thoughts into the minds of producer Hugh Murphy and

the record company executives there. I remember being very happy with how

everything sounded, but clearly, at only 20 years old, I was very

inexperienced.

‘Baker Street’ Clip of early Phil Harding mix

(Archive sound quality)

‘City To City’ Clip of early Phil Harding mix

(Archive sound quality)

Listening

back to my mixes now, I can detect many problems with the balances and choices

made. It is unfortunate that the quality of my tapes has suffered due to

storage conditions, and even though I’ve baked them before digitising there is

a severe lack of high frequencies. Nevertheless, I can define a couple of major

problems...

- The

drums, in particular the kick and snare, are too loud. Certainly, a lot louder

than the balances on the final mixes on the album. I can understand why I would

have balanced the drums like that, because I had spent the last few years

working as assistant engineer on many sessions in Studio 1 with producer Gus Dudgeon

(Elton John mixes, Kiki Dee’s 1974 album ‘I Got The Music In Me’ and many

more). Gus was a big fan of loud drums, as many producers and engineers are,

but for the Gerry Rafferty album, I can now hear that this style of balance was

not appropriate. I don’t remember this being an issue with producer Hugh Murphy

or Gerry, but it was clearly my fault for setting that kind of precedent in the

mixes.

- The balance of the saxophone on ‘Baker Street’ is astonishingly quiet on my mixes compared the loud, strident sound on the final record. Clearly, someone had reviewed these Marquee mixes and made the point that the sax had to be a big feature on ‘Baker Street’, as we all love and know it to be now. That was a big mistake from my end, and whether it was Hugh and Gerry or the record company that pushed for the final balance – or possibly the final mix engineer (Dec O’Doherty at Advision Studios) – it was a stroke of genius, because the final mix from that point of view sounds wonderful and complete.

Other

than those two major points, everything else on my Marquee mixes (vocals/keyboards

and guitars) sound very similar. One of my lasting memories after these

sessions was playing these mixes at full blast in the studio to some of my

musician friends, including Dave Dale, and they were all blown away. Imagine

listening to an unreleased ‘Baker Street’ for the first time, in a fantastic high

quality studio environment! I was inspired that even though the sessions had

moved on elsewhere for remixing, I had done a good job to the best of my

ability at that time. My engineering skills and mixing abilities would improve

from that point on – and the following year, I completed successful mixes for

the Steve Hillage album ‘Open’ (released in 1979) and the huge Amii Stewart hit ‘Knock On Wood’ all in that very same mixing room at The Marquee.

It

has been good for me to reflect on this project, as I had stored my memories of

these sessions together with the tapes for 40+ years without talking or thinking

about them until now. I know from my brief research for this blog that many

people around the world hold this album dearly in their memories. To have been

involved in some small way has truly been a wonderful honour for me. ‘Goldmine Music Collector’s Magazine’ describe it as...

“…One

of the quintessential albums of all time, on an equal footing as The Beatles’

‘Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band’, The Beach Boys’ ‘Pet Sounds’ and Pink

Floyd’s ‘The Dark Side of the Moon’. While Rafferty went on to write and record

further exemplary music, which by no means proved less superior, the immense

commercial success of ‘City to City’, and ‘Baker Street’ overshadowed

everything else he did. It is the one album that will forever be attached to

Rafferty’s legacy as his signature work, and also the one that firmly secured

his place in music history”. (Full article here)

Phil

Harding

September

2021